Contractor Success Resources

Contractor Prequalification: Expert Advice with Arch Insurance

LTIR vs TRIR: Understanding Construction Safety Metrics

The Complete Guide to Serious Injury and Fatality (SIF) Prevention

BIG Construction and the Impact of Strong Partnerships

Keene State College: Educating the Next Generation of Safety Leaders

EMR vs TRIR: A Comparison for Construction Leaders

Strengthen Subcontractor Risk Management with Project-Based Prequalification

How Skanska Navigates a Shifting Modern Construction Landscape

Riley Construction: How Planning & Partnership Deliver Safer Outcomes

Gardner Builders: A Human Approach to Construction

DART vs TRIR: A Complete Guide for Construction Leaders

Inside Frampton Construction: Aligning Safety & Operations

Highwire Recognized in Independent Research Firm Report

The Complete Guide to Contractor Safety Assessments

What is Contractor Success?

Measure What Matters: Tracking Events with SIF-potential

Data Center Safety: Lessons from Industry Leaders

Best B2B Construction Podcasts

Boosting Wrap-Up ROI with Safety Programs

Driving Contractor Success in Mission-Critical Environments

Lessons from T5 - Raising Contractor Standards in the Data Center Race

Rethinking Safety Manuals With Help from AI

How Technology Is Fixing Broken Contractor Insurance Tracking

Understanding Contractor & Construction Safety Ratings

Contractor Prequalification Done Right - Expert Advice from Arch Insurance

Dynamic Movement Strategies - A New Approach to Injury Prevention in Construction

How NOVO Construction Evaluates Subcontractor Risk

Unlock the Power of Inspection Data

Engaging Leadership to Prevent Falls in 2025

Welcome to Highwire's New Podcast, Beyond Prequalification

Understanding and Improving Your Highwire Safety Score

How Turner Construction Builds Safety Culture Through Connection with Emy Marroquin

Leading With Trust: Sean Keaney’s Approach to Safety at Wise Construction

How NTT Global Data Centers Connects Safety Across Every Site with Andrew Boyea

Advancing Data Center Safety: Mark McKeon of Rowan Digital Infrastructure

Adam Board on Building a Culture of Care at T5 Data Centers

Understanding TRIR: What It Is, How to Calculate It, and Why It Matters

Beyond D&B: When and Why to Transition to Contractor Prequalification Systems

The Power of Don't - What Safety Professionals Can Learn from Storytellers

Unlock the Power of Inspection Data

How Hill Crane Elevates Safety Standards with Highwire

The Complete Guide to Subcontractor Prequalification

Beyond Past Incidents: A Better Approach to Contractor Safety

Engaging Leadership to Prevent Falls in 2025

Celebrating Another Year of Excellence: ISO 27001 and SOC 2 Annual Recertification

Enhancing Your Approach To Contractor Risk Management

Wrap-up Profitability - Techniques to improve the success of your CCIP or OCIP

Why Your Contractor Safety Evaluation Process is All Wrong

Exposures to Insights: A Data-Driven Approach to Preventing Fatal Falls

Corrective Action Planning Doesn’t Have To Be Scary

Contractor Prequalification: Your Process Improvement Plan

Shift to SIFs: Measuring & Learning from SIF Exposures

New SIF Tracking Features in Highwire

The Top Four Costs of Enrollment Friction (And How To Minimize Them)

Highwire Safety Badges and Awards

Contractor Spotlight: Berkowsky and Associates, Inc

What GCs Look for in Contractor Assessments

Highwire’s New Mobile App is Live

Boston’s Award-Winning Women-Owned Construction Companies

What is an Experience Modification Rating (EMR) & How to Improve It

From Statistics to Solutions: Addressing Fatal Falls in Construction

Amme Standring, the Director of Safety, Charter Mechanical

Amy McClean, Site Safety Manager, Coffman Excavation

Meet the Safety Team at W. L. French

Meet Steve LaRussa of Google

Don’t Live in the Past: The Power of Leading Indicators in Safety

Four Reasons Specialty Contractors Use Highwire to Assess Subcontractors

Caitlin Bergin, Senior EHS Consultant, BSI Consulting

Client Spotlight: Meet Joan Bremer

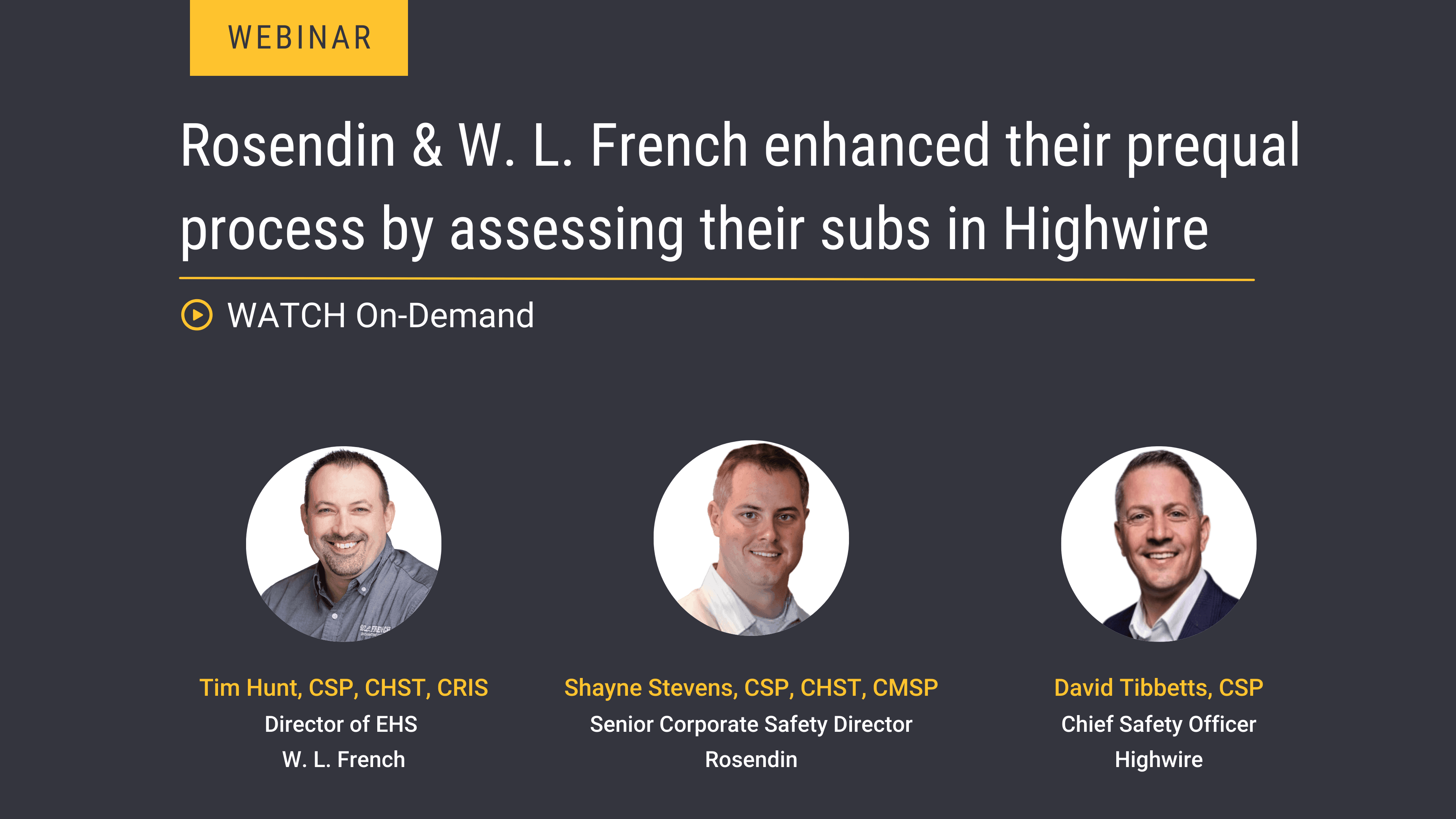

How Rosendin & W. L. French enhanced their prequal process by assessing their subs in Highwire

Meet Veteran-Owned Contractors in The Highwire Network

Highwire’s Commitment to Privacy: The EU General Data Protection Rule

Q&A from “Shift to SIFs: Measuring & Learning from SIF Exposures”

The Myth of the Low Risk Contractor

Four Takeaways from our Roundtable with Google and Lee Kennedy on Measuring & Learning from SIF Exposures

Introducing Highwire’s 2023 Phoenix Safety Award Winners

Building Trust: How Wise Construction’s Safety Culture Drives Repeat Business

Harris Hart: A Legacy of Safety and Innovation

Building a Safety Legacy: Martin Lopez’s Journey at GCON Inc.

Introducing Highwire’s 2023 Philadelphia Safety Award Winners

Contractor Spotlight: Meet SBM Management Services

Introducing Highwire’s 2023 Los Angeles Safety Award Winners

Get Started CCIP and OCIP Profitability: Tips to improve your wrap-up

Driving Safety Culture: The Power of Executive Engagement

Meet Samuel Perez of Torcon

Meet Joshua Johnson of Rosendin Electric

Empowering Safety: Insights from David Watts on Building a Strong Safety Culture at Skanska

Introducing Highwire’s Greater NYC Platinum Safety Award Winners

WIC Week Profile: Pinnacle Construction Services

Meet Women-Owned Contractors (WBE): Elaine Construction Company

Meet Women-Owned Contractors (WBE): Aetna Fire Alarm Service Co., Inc.

Meet Women-Owned Contractors (WBE): Geologic-Earth Exploration

Find Women-Owned Contractors (WBE): American Moving and Installation

Find Women-Owned Contractors (WBE): Hub Glass Services, Inc.

Contractor Prequalification Forms – Benefits & Drawbacks & Free Download

Mental health in the construction industry: the safety risk everyone should be talking

Helmets vs. hardhats: The difference could mean saving a life

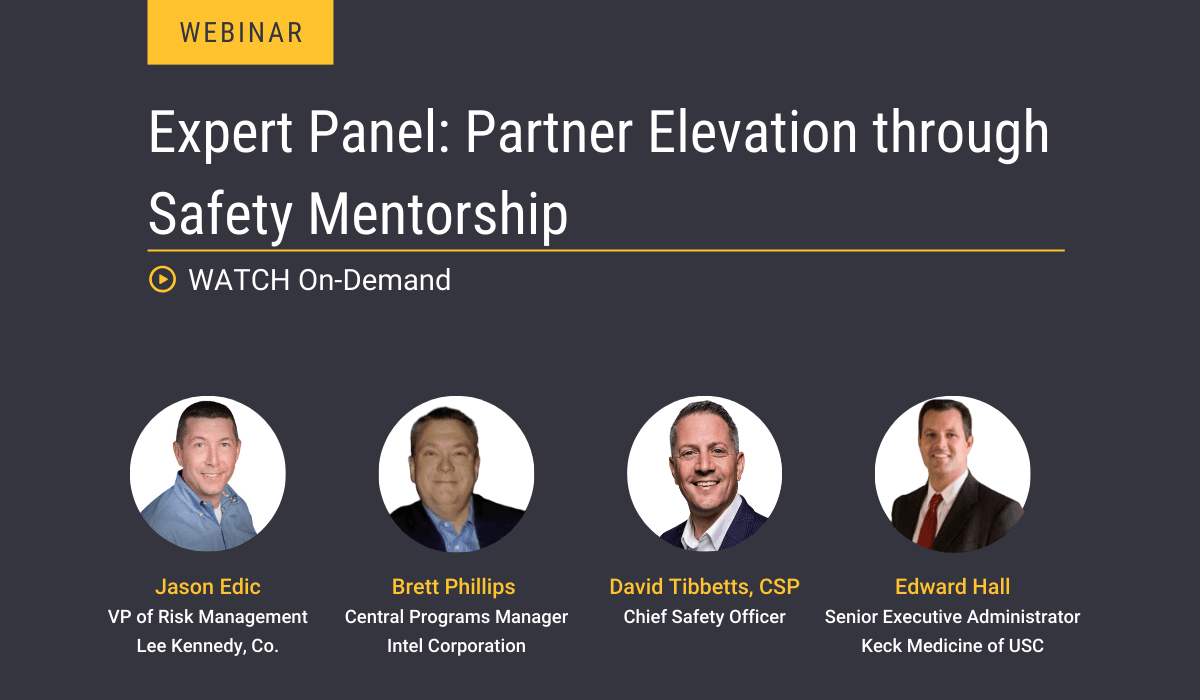

Expert Panel: Partner Elevation through Safety Mentorship